“What time is it on the Clock of the World?”: Immigration and Environmental Justice in the Midwest

For philosopher and civil rights activist Grace Lee Boggs, the Midwest was where she cut her organizing teeth. Her early experiences here animated the connections for her between immigrant justice, environmental justice, and the struggle for equality that would fuel her life’s work. A daughter of Chinese immigrants, Grace Lee Boggs moved to Chicago after completing her Ph.D., inspired by the “distinctly American philosophy of pragmatism” that George Herbert Mead and John Dewey had developed during their time in the city. But upon her arrival, Grace was met with the hostility of racial discrimination, forcing her to take a job that paid just $10 a week while living in rat-infested housing. The conditions prompted her to join a local Black activism group fighting for safe housing conditions in her neighborhood and the rest was, in many ways, history. Boggs’ lifelong commitment to justice was shaped not only by the many communities and struggles she was a part of, but also by the place that she belonged to and her identity as an immigrant in the Midwest.

Grace Lee Boggs’ experience is a reflection the long tradition of immigrants who have been a part of the social fabric of the Midwest, and who have also been leaders in the movements for justice here—especially in environmental justice movements. Today, as the social fabric of our communities is being torn apart by federal violence, the immigrant-led environmental justice networks in the Midwest are rapidly mobilizing on the frontlines of this fight—here’s how.

What We Are Seeing Today

Backed by a July 2025 Supreme Court ruling, Immigration Customs Enforcement (ICE) has drastically expanded their operations this year, using increasingly brutal and violent tactics to detain immigrants, and in many cases detaining United States citizens through racial profiling. Co-workers, neighbors, teachers, students, friends, parents and children dragged off the streets, out of cars and homes–and disappeared. From high school students and teachers in cities across the region including Detroit, Minneapolis and Willmar, parents waiting for their children to get off the school bus at pick up, to longtime employees of local businesses—the brutality of ICE’s tactics have been far reaching across all parts of Midwestern communities.

These operations have also disproportionately impacted Black, Brown, and Indigenous community members, as ICE agents have been emboldened to stop people on the streets and demand to see their documents based on appearance alone. Last month alone, Twin Cities law enforcement leaders reported an influx of complaints to local law enforcement agencies from citizens of color who have been stopped by ICE agents demanding to see their documents during Operation Metro Surge.

As our neighbors are being targeted at work, schools, and in their homes, the impacts of this violence has had a ripple effect across the entire region. One Minneapolis family has been afraid to leave their home for months—forcing them to close down their small business and miss their daughters high school graduation. Midwesterners have been brutalized and killed at the hands of ICE agents, like Chicago father Silvero Villegas-Gonzalez, who many remembered as a “devoted father and a gentle, steady presence in the lives of his children.” The recorded killings of Alex Pretti and Renee Nicole Good by ICE have echoed throughout the country, illustrating the widespread impact of this violence.

But this moment has also revealed the sense of place-based organizing that exists in cities, communities, neighborhoods, and towns across the Midwest has met this time of unspeakable violence with unrelenting love. Everyday acts of care for one another have proven to be an steadfast defense in keeping our neighbors, families, and loved ones safe. No where has this place-based organizing been more readily apparent than in the environmental justice networks that have been able

Responding to Environmental Injustice — Community Organizing Against ICE Raids in the Midwest

COPAL in Minneapolis, Minnesota

Nearly 6 years after the murder of George Floyd in 2020, Minneapolis made international headlines when Renee Good was murdered by an ICE agent on January 7th–just 6 blocks away from where Floyd was killed. Protests have erupted nationally, and the onslaught of ICE raids in Minneapolis intensified throughout the month of January. In the Twin Cities, community members’ tightly organized mutual aid networks protected their neighbors from being detained in the largest ICE operation in the country to date.

This level of community mobilization in the Midwest has taken many by surprise—perhaps best encapsulated by a quote circulating on social media, “nobody thought the revolution would start in Minneapolis…except Prince.” But those of us who call Minneapolis have spent the last half of a decade since George Floyd’s murder building these critical networks to ensure the safety of community members. Similarly, for our partner organizations, this lineage of organizing to ensure community health and safety extends back into the decades spent building environmental justice power in the region.

This is part of why Minneapolis-based partner organizations like COPAL have been poised to respond swiftly to the federal violence we have seen in the past month. Experience launching statewide campaigns like Clean Heat MN, combined with the preexisting infrastructure of social services for Latine immigrant communities across Minnesota, allowed COPAL to quickly mobilize to build the Immigrant Defense Network (IDN) in the wake of the 2024 election. IDN has served as a statewide coalition of over a hundred immigrant, labor, legal, faith and community organizations advocating for the rights of Minnesota immigrants since 2024, and they have now been at the frontlines of community organizing against the largest ICE operation to date. Now, when Minneapolis residents spot ICE agent presence, community members can arrive within minutes to document.

As federal violence has intensified, COPAL and the Immigrant Defense Network have led and organized statewide shows of resistance against ICE operations, including ICE Out of MN, a call on January 23rd for Minnesota communities to pause on work, school, and shopping that brought 100,000 to the streets in Minneapolis amidst subzero temperatures. Now, COPAL is bringing this base-building momentum to cities all across the Midwest through the Brave of Us Tour, providing constitutional observer trainings

the Brave of Us Tour through the Immigrant Defense Network—providing Constitutional Observer trainings in cities all across the Midwest.

LVEJO & PERRO in Chicago, Illinois

Last November, partners in Chicago like Little Village Environmental Justice Organization (LVEJO) and Pilsen Environmental Rights and Reform Organization (PERRO) were doing double duty as they fought to protect their communities from ICE raids and unequal access to public transportation in the city.

The two organizations advocated for continuing public transportation access in their neighborhoods, in particular Chicago’s Pink Line, which was slated to be cut from the route. Nearly half of all Chicagoans that use public transit are BIPOC, and many are also immigrants. As ICE raids swept through the city at the end of last year, this overlap was clear in Chicago’s Little Village and Pilsen neighborhoods. Community events around the Pink Line organized by LVEJO and PERRO that had 100 RSVPS saw attendance dwindle—in the end, only 30 people showed up due to ICE presence. In response, PERRO’s President Citlalli Trujillo stated that they shifted all of their attention and resources to helping out their community members.

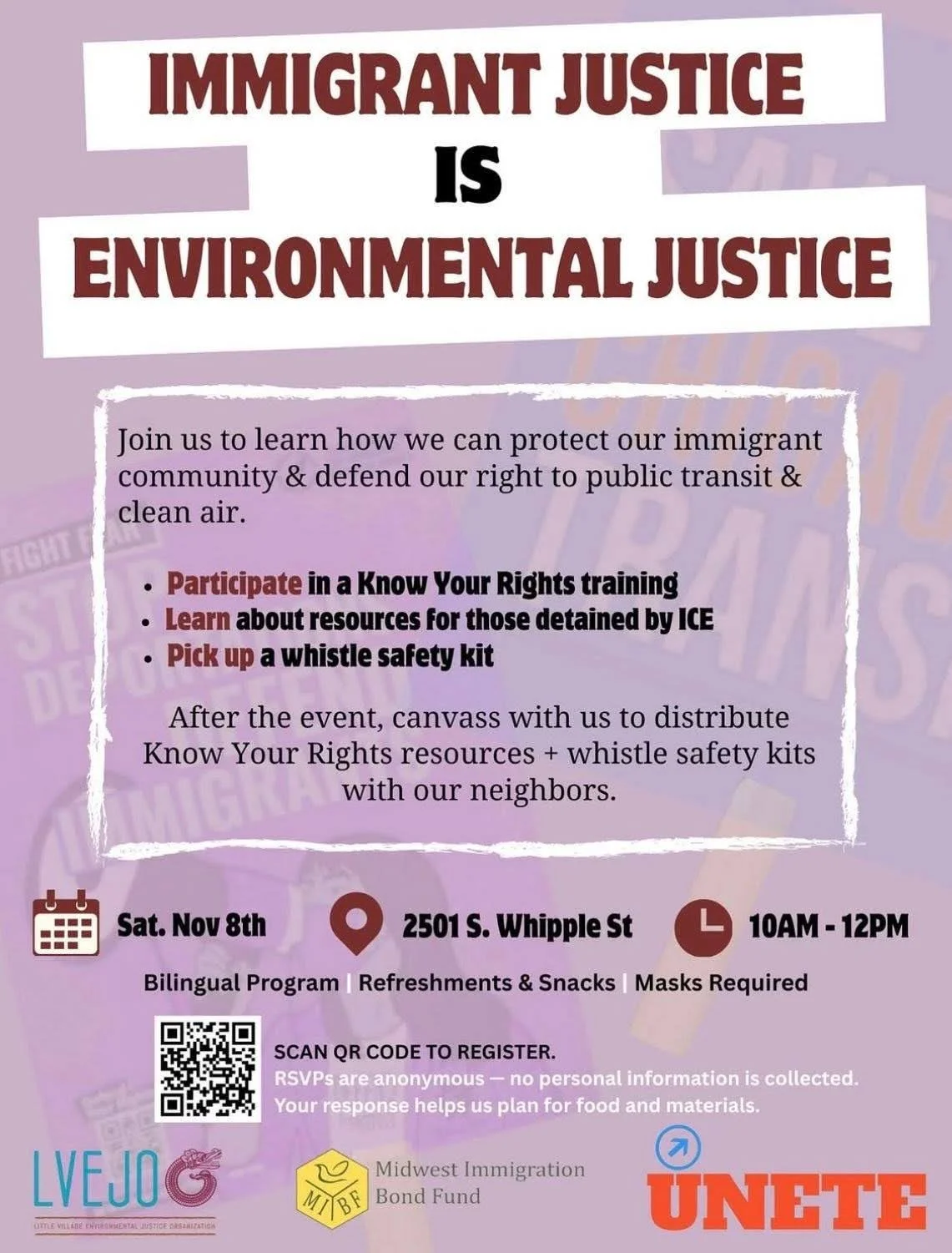

As ICE spent nearly 3 months in 2025 heavily policing and terrorizing Chicago neighborhoods, and detaining around 4,200 Chicago residents, LVEJO organized rapid response teams to protect community members. An educational environmental justice gathering was interrupted when LVEJO responded to ICE violence on November 8, 2025, prompting them to shift their focus to hosting a ‘Know Your Rights’ workshop, which provided resources on what to do if someone you know has been detained by ICE and included whistle kits to pick up. This community organizing was quickly followed up with city and state-level advocacy. In response to the increased ICE violence in the city, LVEJO drafted a statement addressed to the Governor and the Chicago Transportation Authority urging them to protect public transportation from ICE agents as public transport was being targeted, and urged the city transportation authorities to refuse any federal funding that requires cooperation with immigration enforcement.

This is Not the Beginning nor the End

League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC)’s long-standing immigrant rights work in Iowa reminds us that the fight for safety and for a better future has been an ongoing battle that did not start this year.

In 1910 there were less than 600 Latino immigrants in the entire state of Iowa. By 1920, there were more than 2,500. Mostly from Mexico, immigrants worked as farm laborers and others worked in railroad yards, particularly in West Des Moines. The expansion of meatpacking facilities all over Iowa since the late 1980s has attracted Mexican immigrant wage laborers. In 2000, 70 percent of the production workers at the Swift and Company plant in Marshalltown were Latinos.

Upon their arrival to the Midwest, many immigrants faced housing discrimination, workers rights abuses and racism. To protect themselves and their loved ones they organized. LULAC has fought for education rights for children, voting rights, and against workplace and housing discrimination. Over the years, LULAC has also responded to Immigration Enforcement violence. In 2018, they responded to ICE raids at a concrete facility that took 32 workers near Mt. Pleasant Iowa. They searched for those who had been detained. In 2020, as a part of a coalition, LULAC advocated for the release of detained people who were most vulnerable to COVID-19.

They have established networks for response as a result of previous years of ICE presence and are doing response training with young leaders. They continue to do the hard, long-standing work to provide support for people who are looking to make Iowa their home.

Environmental justice and immigrant justice advocates have long known that their struggles are one in the same. When the land, the water, the air around BIPOC communities are treated as disposable, when immigrant neighbors are treated as removable, and when the federal government tries to bully people into silence– EJ communities always remind the world of the depths of their love for their places and their people. The actions of LVEJO, PERRO, COPAL, and LULAC are emblematic of the type of organizing that is happening here in the Midwest—capable of breathing hope into the communities even in the darkest of moments, and demanding accountability from the perpetrators.

Towards the end of her life, Boggs wrote of the importance of a place-based consciousness as a powerful organizing tool because it “encourages us to come together around common, local experiences and organize around our hopes for the future of our communities and cities.” Boggs also reminded us that revolutions are born of love. In LVEJO, COPAL, LULAC, and other immigrant-led environmental justice orgs across the Midwest we see the greatest and bravest acts of love–lighting the path towards a safer, brighter future, grounded in a deep love of this place where we come together.